|

|

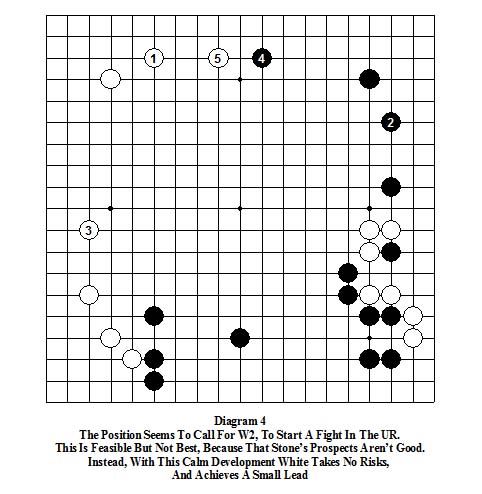

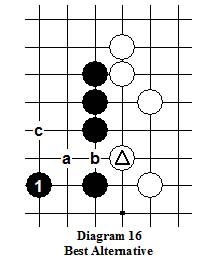

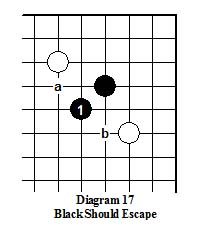

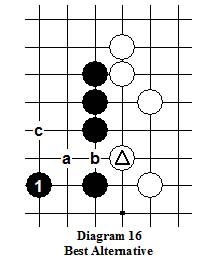

Diagram 16 So after further reflection, the one point skip of B1 here is revealed as the move that best accomplishes all of Black’s objectives!

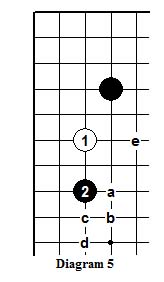

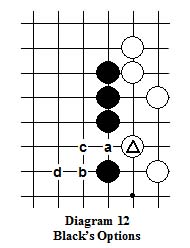

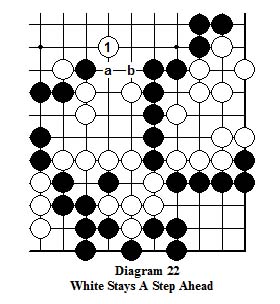

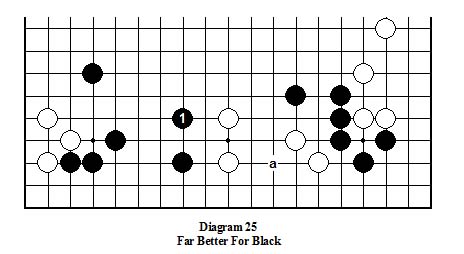

After this, if White makes the shape-killing placement at “a”, B “b” connects efficiently because W“a” is now almost trapped.

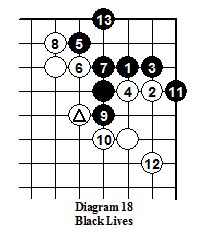

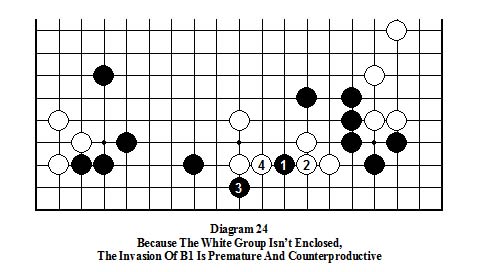

After that, playing immediately (as at “c”) to rescue W“a” would only help Black. Not only would he then have a larger White group to attack, but (assuming the relatively open center we noted at the outset)

that newly formed White group will probably not seriously threaten Black because those White stones will almost certainly be weaker than the Blacks they are supposedly attacking.

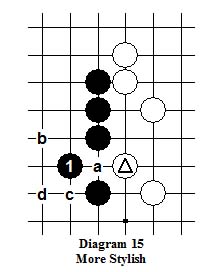

If after B1, instead of W“a” White pushes at “b”, with B“a” the position reverts to Dia 15 after W“a”, B“d’ there.

After W“a”, B“b”, if White doesn’t extend from “a”, then if and when appropriate, B“c”(or even a more distant Geta) is a further stylish play that assures that W“a”is trapped, almost certainly yielding Black one eye.

|